The forums › Quizz, Fav TV, Fav Music, Fav Films, Books… › What do you think about… The discussion thread

- This topic has 175 replies, 23 voices, and was last updated 10 years, 2 months ago by jayc.

-

AuthorPosts

-

September 16, 2014 at 2:26 pm #78376Anonymous

Hmmmm i know how it feels when others open her mouth before they think,i am from germany and we Germans wear a sign a Long time now……

September 17, 2014 at 12:39 pm #78377The views on the Confederate Flag is a complicated subject for most Americans. It's a topic that can often get heated and tense considering the history behind the flag.

I typically judge the display(ers) of the flag individually, depending less on the popular generalizations of the day, associated with bearers of the flag. What I have learned is that a reasonable, and even understandable argument can be made for displaying the flag. If the argument is made that it represents Southern culture and identity, then that's reasonable enough. If the argument is made that it represents peaceful dissent against a growing Federal (U.S) government that is over stepping its bounds and must be checked (the rebels I respect), then that is fair enough. The last point especially is an admirable point; one that I find difficult to argue against, considering the recent expansion of Federal authority here in the U.S.

However, it is also completely understandable to see why so many people (particularly those who are African American) have an issue with the flag being displayed. It may have evolved to mean Southern autonomy, state rights and Independence, and a spirited rebellious attitude, but for many it means only one thing: an approval of slavery. Again current bearers of old Dixie may have moved away from racial aspects of the flag it once represented and instead focus more on what I consider just reasons for displaying the flag, but at the end of the day, it is a difficult to overlook the dark history surrounding it; one that provided a despicable justification for slavery (hiding behind the protective shroud of free, hyper Capitalism and state rights).

It's with this aforementioned aspect that I personally struggle with the most. I often wonder if the other positive justifications for displaying the flag are out weighed heavily by the tragic choice the Confederacy made with the issue of slavery. Is this point alone enough to warrant an abandonment of the flag (on a public/state level at least)? That's a question that I often ask or asked when discussing this topic of the flag.

Having said all that, I do agree with most that the meaning behind the flag has changed and that we must be careful in judging those who display it. They have a right to display the flag. I also wouldn't consider most who do wave it proudly, racist.

At the same time, I say to those who do display the flag to be aware of the complex racial undertones it does bring, and to be mindful of that fact when engaging with those -who in my opinion- have just cause to be taken aback by its display.

September 18, 2014 at 1:01 am #78378Dear roxy the flag you just posted was used on the high seas for slavery ships.

September 18, 2014 at 3:17 am #78379on that note im glad to see we all can agree to disagree

September 18, 2014 at 8:03 am #78380Sheza

on that note im glad to see we all can agree to disagree

Yes. That's one idea of this topic. To discuss, to exchange opinions and experiences and also to agree to disagree sometimes. From the current discussion I have learned a lot about the american flags.

September 18, 2014 at 8:18 am #78381This is quite an interesting discussion. Thank you all for taking part and teaching us about american history.

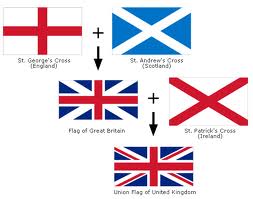

A few years back, a certain section of the English society tried to take the Union Jack and make it theirs. It started to represent undertones of racism, against foreigners in our lands.

We didn't let them. We took our flag back. The Flag is that of the United Kingdom.

Which brings me to another important day in our History.

Scotland are voting today for independence.

[img]https://encrypted-tbn3.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcS6GZGBUkUhYCZnIn-GYyznZhQn9e2ooGTOMwxoAlOJVqYq1LDA[/img]

We could lose our Union Jack forever.

It would have to be re-designed. Maybe something like this.

Good Luck to all the people of Scotland in such an important decision.

I hope you stay with us. I really do. You are family.

September 18, 2014 at 8:37 am #78382never again will I post a opinion ,never again will I say I will never be racist towards certain people ner again will I buy achat again for this is what I get for voiceing a opinion

CHAT LOG THAT WAS PUBLISHED HERE WAS REMOVED. MODERATED BY BRANDYBEE

September 18, 2014 at 9:11 am #78383xShezawolfx

Everyone is welcome here to voice an opinion and open up a discussion. I am enjoying this topic very much and am being educated about American history.

For that I believe it to be of interest and a successful subject to discuss. Well done for bringing up the matter for discussion.When there are strong feelings on subjects of course you will get opposing views. But that is, what makes us individual. And in hearing others views it educates and teaches tolerance.

If your topic or subject is provoking abuse, then please report it to Achat or us Moderators. We will not advocate abuse of any sort.

The chatlog you published was abusive and has been forwarded to Achat for investigation. In future, please forward by PM. Do not publish in topics as it detracts from the subject discussed. In this case, Flag waving.

Back to topic please… I am interested in others views on this …

September 18, 2014 at 2:45 pm #78384I have no more views,no thought all that stuff that I posted and I knew I was breaking tos rules,not once did I swear not once did I call her out of name but though all that I did learn something,people wont belive anyother version be it the truth or indifferent no matter how much you show ortell

September 18, 2014 at 2:58 pm #78385We have to separate several aspects now.

– We have the discussion about flags now. A good discussion, which I like and hope to continue. I won't accept anybody voicing his opinion regarding flags will be threatened or offended, as long as his arguments are factual of course.

– There is something going on in background with you and some other members. This is nothing for an open discussion in forum. The forum is not a place to start or continue private argues. This we won't accept here, but offer our help to mediate or/and to bring it up to A-Team.

September 18, 2014 at 3:37 pm #78386Flags of the ConfederacyThe Confederate States of America adopted three different national flag patterns between 1861 and 1865. The Provisional Confederate Congress adopted the First National pattern, also referred to as the “Stars and Bars”, on March 4, 1861. This pattern flag flew over the Capitol at Montgomery, Alabama, where the Provisional Congress met prior to the bombardment of Fort Sumter in April 1861.

The Second National pattern, also referred to as the “Stainless Banner”, was adopted May 1, 1863 and incorporated the Army of Northern Virginia’s battle flag design in the canton on a white field. The first official use of the Second National pattern flag was on Stonewall Jackson's casket when his body lay in state in Richmond, May 10, 1863.

The Third National pattern, adopted March 4, 1865, shortened the white field and added a vertical red bar to the end of the Second National pattern flag. Very few, if any, of the Third National pattern flags saw service during the war, since General Lee's Army of Northern Virginia surrendered just a few weeks later at Appomattox.

In addition to the national flags of the Confederacy, there were many battle flag patterns used by the Confederate armies.

The Army of Northern Virginia pattern battle flag, first issued to units beginning in November 1861, was designed to be a distinctive flag for use on the battlefield. It underwent numerous revisions in design and materials throughout the war. Although this particular flag is the most common flag pattern associated with the Confederate States of America, the Confederate Congress never officially adopted this flag, except as the canton of the Second and Third National patterns.

taken from: http://www.moc.org/collections-archives/flags-confederacy

In my opinion, the two main reasons why the battle flag is offensive to many:

1. It represents the south's desire to continue the “peculiar institution” which was a euphemism for slavery. When you prune all the causes of the American Civil War to it's roots, slavery is what remains. Some will argue it was for state's rights, but that right they speak of was linked to slavery.

2. In almost every picture or depiction of white supremacy groups, such as the Klu Klux Klan, that battle flag is usually present.

September 18, 2014 at 9:50 pm #78387NORTHERN PROFITS from SLAVERY

The effects of the New England slave trade were momentous. It was one of the foundations of New England's economic structure; it created a wealthy class of slave-trading merchants, while the profits derived from this commerce stimulated cultural development and philanthropy. –Lorenzo Johnston Greene, �The Negro in Colonial New England, 1620-1776,� p.319.

Whether it was officially encouraged, as in New York and New Jersey, or not, as in Pennsylvania, the slave trade flourished in colonial Northern ports. But New England was by far the leading slave merchant of the American colonies.

The first systematic venture from New England to Africa was undertaken in 1644 by an association of Boston traders, who sent three ships in quest of gold dust and black slaves. One vessel returned the following year with a cargo of wine, salt, sugar, and tobacco, which it had picked up in Barbados in exchange for slaves. But the other two ran into European warships off the African coast and barely escaped in one piece. Their fate was a good example of why Americans stayed out of the slave trade in the 17th century. Slave voyages were profitable, but Puritan merchants lacked the resources, financial and physical, to compete with the vast, armed, quasi-independent European chartered corporations that were battling to monopolize the trade in black slaves on the west coast of Africa. The superpowers in this struggle were the Dutch West India Company and the English Royal African Company. The Boston slavers avoided this by making the longer trip to the east coast of Africa, and by 1676 the Massachusetts ships were going to Madagascar for slaves. Boston merchants were selling these slaves in Virginia by 1678. But on the whole, in the 17th century New Englanders merely dabbled in the slave trade.Then, around 1700, the picture changed. First the British got the upper hand on the Dutch and drove them from many of their New World colonies, weakening their demand for slaves and their power to control the trade in Africa. Then the Royal African Company's monopoly on African coastal slave trade was revoked by Parliament in 1696. Finally, the Assiento and the Treaty of Utrecht (1713) gave the British a contract to supply Spanish America with 4,800 slaves a year. This combination of events dangled slave gold in front of the New England slave traders, and they pounced. Within a few years, the famous �Triangle Trade� and its notorious �Middle Passage� were in place.

Rhode Islanders had begun including slaves among their cargo in a small way as far back as 1709. But the trade began in earnest there in the 1730s. Despite a late start, Rhode Island soon surpassed Massachusetts as the chief colonial carrier. After the Revolution, Rhode Island merchants had no serious American competitors. They controlled between 60 and 90 percent of the U.S. trade in African slaves. Rhode Island had excellent harbors, poor soil, and it lacked easy access to the Newfoundland fisheries. In slave trading, it found its natural calling. William Ellery, prominent Newport merchant, wrote in 1791, �An Ethiopian could as soon change his skin as a Newport merchant could be induced to change so lucrative a trade as that in slaves for the slow profits of any manufactory.�[1]

Boston and Newport were the chief slave ports, but nearly all the New England towns — Salem, Providence, Middletown, New London � had a hand in it. In 1740, slaving interests in Newport owned or managed 150 vessels engaged in all manner of trading. In Rhode Island colony, as much as two-thirds of the merchant fleet and a similar fraction of sailors were engaged in slave traffic. The colonial governments of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania all, at various times, derived money from the slave trade by levying duties on black imports. Tariffs on slave import in Rhode Island in 1717 and 1729 were used to repair roads and bridges.

The 1750 revocation of the Assiento dramatically changed the slave trade yet again. The system that had been set up to stock Spanish America with thousands of Africans now needed another market. Slave ships began to steer northward. From 1750 to 1770, African slaves flooded the Northern docks. Merchants from Philadelphia, New York, and Perth Amboy began to ship large lots (100 or more) in a single trip. As a result, wholesale prices of slaves in New York fell 50% in six years.

On the eve of the Revolution, the slave trade �formed the very basis of the economic life of New England.�[2] It wove itself into the entire regional economy of New England. The Massachusetts slave trade gave work to coopers, tanners, sailmakers, and ropemakers. Countless agents, insurers, lawyers, clerks, and scriveners handled the paperwork for slave merchants. Upper New England loggers, Grand Banks fishermen, and livestock farmers provided the raw materials shipped to the West Indies on that leg of the slave trade. Colonial newspapers drew much of their income from advertisements of slaves for sale or hire. New England-made rum, trinkets, and bar iron were exchanged for slaves. When the British in 1763 proposed a tax on sugar and molasses, Massachusetts merchants pointed out that these were staples of the slave trade, and the loss of that would throw 5,000 seamen out of work in the colony and idle almost 700 ships. The connection between molasses and the slave trade was rum. Millions of gallons of cheap rum, manufactured in New England, went to Africa and bought black people. Tiny Rhode Island had more than 30 distilleries, 22 of them in Newport. In Massachusetts, 63 distilleries produced 2.7 million gallons of rum in 1774. Some was for local use: rum was ubiquitous in lumber camps and on fishing ships. �But primarily rum was linked with the Negro trade, and immense quantities of the raw liquor were sent to Africa and exchanged for slaves. So important was rum on the Guinea Coast that by 1723 it had surpassed French and Holland brandy, English gin, trinkets and dry goods as a medium of barter.�[3] Slaves costing the equivalent of �4 or �5 in rum or bar iron in West Africa were sold in the West Indies in 1746 for �30 to �80. New England thrift made the rum cheaply — production cost was as low as 5� pence a gallon — and the same spirit of Yankee thrift discovered that the slave ships were most economical with only 3 feet 3 inches of vertical space to a deck and 13 inches of surface area per slave, the human cargo laid in carefully like spoons in a silverware case.

A list of the leading slave merchants is almost identical with a list of the region's prominent families: the Fanueils, Royalls, and Cabots of Massachusetts; the Wantons, Browns, and Champlins of Rhode Island; the Whipples of New Hampshire; the Eastons of Connecticut; Willing & Morris of Philadelphia. To this day, it's difficult to find an old North institution of any antiquity that isn't tainted by slavery. Ezra Stiles imported slaves while president of Yale. Six slave merchants served as mayor of Philadelphia. Even a liberal bastion like Brown University has the shameful blot on its escutcheon. It is named for the Brown brothers, Nicholas, John, Joseph, and Moses, manufacturers and traders who shipped salt, lumber, meat — and slaves. And like many business families of the time, the Browns had indirect connections to slavery via rum distilling. John Brown, who paid half the cost of the college's first library, became the first Rhode Islander prosecuted under the federal Slave Trade Act of 1794 and had to forfeit his slave ship. Historical evidence also indicates that slaves were used at the family's candle factory in Providence, its ironworks in Scituate, and to build Brown's University Hall.[4]

Even after slavery was outlawed in the North, ships out of New England continued to carry thousands of Africans to the American South. Some 156,000 slaves were brought to the United States in the period 1801-08, almost all of them on ships that sailed from New England ports that had recently outlawed slavery. Rhode Island slavers alone imported an average of 6,400 Africans annually into the U.S. in the years 1805 and 1806. The financial base of New England's antebellum manufacturing boom was money it had made in shipping. And that shipping money was largely acquired directly or indirectly from slavery, whether by importing Africans to the Americas, transporting slave-grown cotton to England, or hauling Pennsylvania wheat and Rhode Island rum to the slave-labor colonies of the Caribbean.

Northerners profited from slavery in many ways, right up to the eve of the Civil War. The decline of slavery in the upper South is well documented, as is the sale of slaves from Virginia and Maryland to the cotton plantations of the Deep South. But someone had to get them there, and the U.S. coastal trade was firmly in Northern hands. William Lloyd Garrison made his first mark as an anti-slavery man by printing attacks on New England merchants who shipped slaves from Baltimore to New Orleans.

Long after the U.S. slave trade officially ended, the more extensive movement of Africans to Brazil and Cuba continued. The U.S. Navy never was assiduous in hunting down slave traders. The much larger British Navy was more aggressive, and it attempted a blockade of the slave coast of Africa, but the U.S. was one of the few nations that did not permit British patrols to search its vessels, so slave traders continuing to bring human cargo to Brazil and Cuba generally did so under the U.S. flag. They also did so in ships built for the purpose by Northern shipyards, in ventures financed by Northern manufacturers.

In a notorious case, the famous schooner-yacht Wanderer, pride of the New York Yacht Club, put in to Port Jefferson Harbor in April 1858 to be fitted out for the slave trade. Everyone looked the other way — which suggests this kind of thing was not unusual — except the surveyor of the port, who reported his suspicions to the federal officials. The ship was seized and towed to New York, but her captain talked (and possibly bought) his way out and was allowed to sail for Charleston, S.C.

Fitting out was completed there, the Wanderer was cleared by Customs, and she sailed to Africa where she took aboard some 600 blacks. On Nov. 28, 1858, she reached Jekyll Island, Georgia, where she illegally unloaded the 465 survivors of what is generally called the last shipment of slaves to arrive in the United States.

So lets stop saying slavery was a Southern thing http://slavenorth.com/profits.htmSeptember 19, 2014 at 12:17 pm #78388The institution of slavery was firmly established in the American colonies by the time of the American Revolution. The total of a half million slaves were spread out through all of the colonies, but It was most important in the six southern states from Maryland to Georgia. 40% of the South’s population was made up of slaves, and as Americans moved into Kentucky and the rest of the southwest fully one-sixth of the settlers were slaves. By the end of the war, the New England states provided most of the American ships that were used in the foreign slave trade while most of their customers were in Georgia and the Carolinas.

During this time many Americans found it difficult to reconcile slavery with their interpretation of Christianity and the lofty sentiments that flowed from the Declaration of Independence. A small antislavery movement, led by the Quakers, had some impact in the 1780s and by the late 1780s all of the states except for Georgia had placed some restrictions on their participation in slave trafficking. Still, no serious national political movement against slavery developed, largely due to the overriding concern over achieving national unity. When the Constitutional Convention met, slavery was the one issue that left the least possibility of compromise, the one that would most pit morality against pragmatism. In the end, while many would take comfort in the fact that the word slavery never occurs in the Constitution, critics note that the three-fifths clause* provided slaveholders with extra representatives in Congress, the requirement of the federal government to suppress domestic violence would dedicate national resources to defending against slave revolts, a twenty-year delay in banning the import of slaves allowed the South to fortify its labor needs, and the amendment process made the national abolition of slavery very unlikely in the foreseeable future.

With the outlawing of the African slave trade on January 1, 1808, many Americans felt that the slavery issue was resolved. Any national discussion that might have continued over slavery was drowned out by the years of trade embargoes, maritime competition with Great Britain and France, and, finally, the War of 1812 (when the United States once again kicked Great Britain’s ass

). The one exception to this quiet regarding slavery was the New Englanders' association of their frustration with the war with their resentment of the three-fifths clause that seemed to allow the South to dominate national politics.

). The one exception to this quiet regarding slavery was the New Englanders' association of their frustration with the war with their resentment of the three-fifths clause that seemed to allow the South to dominate national politics.In the aftermath of the American Revolution, the northern states (north of the Mason-Dixon Line separating Pennsylvania and Maryland) abolished slavery by 1804. The Mason-Dixon Line runs east through the southern part of New Jersey, so yes… there were slaves in the North. In the 1787 Northwest Ordinance, Congress (still under the Articles of Confederation) barred slavery from the Mid-Western territory north of the Ohio River, but when the U.S. Congress organized the southern territories acquired through the Louisiana Purchase, the ban on slavery was omitted.

* The Three-Fifths Compromise

The Three-Fifths Compromise was a compromise reached between delegates from southern states and those from northern states during the 1787 United States Constitutional Convention. The debate was over if, and if so, how, slaves would be counted when determining a state's total population for constitutional purposes. The issue was important, as this population number would then be used to determine the number of seats that the state would have in the United States House of Representatives for the next ten years, and to determine what percentage of the nation's direct tax burden the state would have to bear. The compromise was proposed by delegates James Wilson and Roger Sherman.The Convention had unanimously accepted the principle that representation in the House of Representatives would be in proportion to the relative state populations. However, since slaves could not vote, non-slaves in slave states would thus have the benefit of increased representation in the House and the Electoral College. Delegates opposed to slavery proposed that only free inhabitants of each state be counted for apportionment purposes, while delegates supportive of slavery, on the other hand, opposed the proposal, wanting slaves to count in their actual numbers. A compromise which was finally agreed upon—of counting “all other persons” as only three-fifths of their actual numbers—reduced the representation of the slave states relative to the original proposals, but improved it over the Northern position. An inducement for slave states to accept the Compromise was its tie to taxation in the same ratio, so that the burden of taxation on the slave states was also reduced.

The Three-Fifths Compromise is found in Article 1, Section 2, Paragraph 3 of the United States Constitution which reads:

Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons.

September 19, 2014 at 12:25 pm #78389TY

September 19, 2014 at 1:07 pm #78390Most Americans are or should be aware of the past history the Union had with slavery. If you're making the argument that the U.S flag should share the same level of guilt and shame like that of the Confederate flag because of its association with slavery (or if you're making the argument that we should abandon all arguments that one is more righteous over another and simply enjoy the flags any which way we want without relying on past history), then I say I find a fault in your logic.

The difference between both the Confederacy and the Union is this: slavery was only a part of the history to the latter, while it was the entire history of the former, because the Confederacy ultimately dissolved with the end of the Civil War. To use an idea from Sartre, “An entity is defined by what it does during its existence, and nothing else”. The Confederacy lived and died, and during its existence, always stood for the full-throat, violent defense of slavery. The U.S were and still is, given that opportunity to change, shift policies and correct mistakes much like every individual has that right to redeem themselves. Essentially, the U.S flag has the luxury to move away from past mistakes (in this case slavery) because it has survived long enough to correct those mistakes, unlike the Confederacy which doesn't have that same opportunity.

If we were to go by your logic (again the one I think you are insinuating) then all flags, be it American, French, or British would carry no honor or virtue because of their past historical mistakes. These nations and the flags that represent them, are still able to aspire to the ideals that make them virtuous.

I am sorry if that doesn't seem fair. If others may feel that the Confederate flag should have that same right as other flags to shift away from any negative symbolic connotations and focus more on the positive connotations it does have. To diminish the subject of slavery -one of the defining legacies the Confederacy has- is an attempt to rewrite history.

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.

Optimizing new Forum... Try it, and report bugs to support.

The forums › Quizz, Fav TV, Fav Music, Fav Films, Books… › What do you think about… The discussion thread

). The one exception to this quiet regarding slavery was the New Englanders' association of their frustration with the war with their resentment of the three-fifths clause that seemed to allow the South to dominate national politics.

). The one exception to this quiet regarding slavery was the New Englanders' association of their frustration with the war with their resentment of the three-fifths clause that seemed to allow the South to dominate national politics.